ast May, Luis Miguel Rojas-Berscia, a doctoral candidate at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, in the Dutch city of Nijmegen, flew to Malta for a week to learn Maltese. He had a hefty grammar book in his backpack, but he didn’t plan to open it unless he had to. “We’ll do this as I would in the Amazon,” he told me, referring to his fieldwork as a linguist. Our plan was for me to observe how he went about learning a new language, starting with “hello” and “thank you.”

Rojas-Berscia is a twenty-seven-year-old Peruvian with a baby face and spiky dark hair. A friend had given him a new pair of earrings, which he wore on Malta with funky tank tops and a chain necklace. He looked like any other laid-back young tourist, except for the intense focus—all senses cocked—with which he takes in a new environment. Linguistics is a formidably cerebral discipline. At a conference in Nijmegen that had preceded our trip to Malta, there were papers on “the anatomical similarities in the phonatory apparati of humans and harbor seals” and “hippocampal-dependent declarative memory,” along with a neuropsychological analysis of speech and sound processing in the brains of beatboxers. Rojas-Berscia’s Ph.D. research, with the Shawi people of the Peruvian rain forest, doesn’t involve fMRI data or computer modelling, but it is still arcane to a layperson. “I’m developing a theory of language change called the Flux Approach,” he explained one evening, at a country inn outside the city, over the delicious pannenkoeken (pancakes) that are a local specialty. “A flux is a dynamism that involves a social fact and an impact, either functionally or formally, in linguistic competence.”

Linguistic competence, as it happens, was the subject of my own interest in Rojas-Berscia. He is a hyperpolyglot, with a command of twenty-two living languages (Spanish, Italian, Piedmontese, English, Mandarin, French, Esperanto, Portuguese, Romanian, Quechua, Shawi, Aymara, German, Dutch, Catalan, Russian, Hakka Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Guarani, Farsi, and Serbian), thirteen of which he speaks fluently. He also knows six classical or endangered languages: Latin, Ancient Greek, Biblical Hebrew, Shiwilu, Muniche, and Selk’nam, an indigenous tongue of Tierra del Fuego, which was the subject of his master’s thesis. We first made contact three years ago, when I was writing about a Chilean youth who called himself the last surviving speaker of Selk’nam. How could such a claim be verified? Pretty much only, it turned out, by Rojas-Berscia.

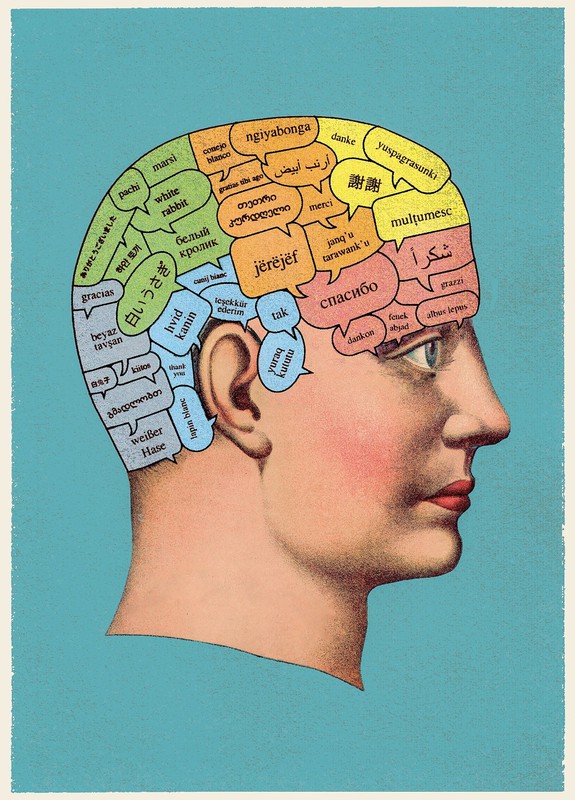

Superlative feats have always thrilled average mortals, in part, perhaps, because they register as a victory for Team Homo Sapiens: they redefine the humanly possible. If the ultra-marathoner Dean Karnazes can run three hundred and fifty miles without sleep, he may inspire you to jog around the block. If Rojas-Berscia can speak twenty-two languages, perhaps you can crank up your high-school Spanish or bat-mitzvah Hebrew, or learn enough of your grandma’s Korean to understand her stories. Such is the promise of online language-learning programs like Pimsleur, Babbel, Rosetta Stone, and Duolingo: in the brain of every monolingual, there’s a dormant polyglot—a genie—who, with some brisk mental friction, can be woken up. I tested that presumption at the start of my research, signing up on Duolingo to learn Vietnamese. (The app is free, and I was curious about the challenges of a tonal language.) It turns out that I’m good at hello—chào—but thank you, cảm ơn, is harder.

The word “hyperpolyglot” was coined two decades ago, by a British linguist, Richard Hudson, who was launching an Internet search for the world’s greatest language learner. But the phenomenon and its mystique are ancient. In Acts 2 of the New Testament, Christ’s disciples receive the Holy Spirit and can suddenly “speak in tongues” (glōssais lalein, in Greek), preaching in the languages of “every nation under heaven.” According to Pliny the Elder, the Greco-Persian king Mithridates VI, who ruled twenty-two nations in the first century B.C., “administered their laws in as many languages, and could harangue in each of them.” Plutarch claimed that Cleopatra “very seldom had need of an interpreter,” and was the only monarch of her Greek dynasty fluent in Egyptian. Elizabeth I also allegedly mastered the tongues of her realm—Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, and Irish, plus six others.

With a mere ten languages, Shakespeare’s Queen does not qualify as a hyperpolyglot; the accepted threshold is eleven. The prowess of Giuseppe Mezzofanti (1774-1849) is more astounding and better documented. Mezzofanti, an Italian cardinal, was fluent in at least thirty languages and studied another forty-two, including, he claimed, Algonquin. In the decades that he lived in Rome, as the chief custodian of the Vatican Library, notables from around the world dropped by to interrogate him in their mother tongues, and he flitted as nimbly among them as a bee in a rose garden. Lord Byron, who is said to have spoken Greek, French, Italian, German, Latin, and some Armenian, in addition to his immortal English, lost a cursing contest with the Cardinal and afterward, with admiration, called him a “monster.” Other witnesses were less enchanted, comparing him to a parrot. But his gifts were certified by an Irish scholar and a British philologist, Charles William Russell and Thomas Watts, who set a standard for fluency that is still useful in vetting the claims of modern Mezzofantis: Can they speak with an unstilted freedom that transcends rote mimicry?

Mezzofanti, the son of a carpenter, picked up Latin by standing outside a seminary, listening to the boys recite their conjugations. Rojas-Berscia, by contrast, grew up in an educated trilingual household. His father is a Peruvian businessman, and the family lives comfortably in Lima. His mother is a shop manager of Italian origin, and his maternal grandmother, who cared for him as a boy, taught him Piedmontese. He learned English in preschool and speaks it impeccably, with the same slight Latin inflection—a trill of otherness, rather than an accent—that he has in every language I can vouch for. Maltese had been on his wish list for a while, along with Uighur and Sanskrit. “What happens is this,” he said, over dinner at a Chinese restaurant in Nijmegen, where he was chatting in Mandarin with the owner and in Dutch with a server, while alternating between French and Spanish with a fellow-student at the institute. “I’m an amoureux de langues. And, when I fall in love with a language, I have to learn it. There’s no practical motive—it’s a form of play.” An amoureux, one might note, covets his beloved, body and soul.

My own modest competence in foreign languages (I speak three) is nothing to boast of in most parts of the world, where multilingualism is the norm. People who live at a crossroads of cultures—Melanesians, South Asians, Latin-Americans, Central Europeans, sub-Saharan Africans, plus millions of others, including the Maltese and the Shawi—acquire languages without considering it a noteworthy achievement. Leaving New York, on the way to the Netherlands, I overheard a Ghanaian taxi-driver chatting on his cell phone in a tonal language that I didn’t recognize. “It’s Hausa,” he told me. “I speak it with my father, whose family comes from Nigeria. But I speak Twi with my mom, Ga with my friends, some Ewe, and English is our lingua franca. If people in Chelsea spoke one thing and people in SoHo another, New Yorkers would be multilingual, too.”

Linguistically speaking, that taxi-driver is a more typical citizen of the globe than the average American is. Consider Adul Sam-on, one of the teen-age soccer players rescued last July from the cave in Mae Sai, Thailand. Adul grew up in dire poverty on the porous Thai border with Myanmar and Laos, where diverse populations intersect. His family belongs to an ethnic minority, the Wa, who speak an Austroasiatic language that is also widespread in parts of China. In addition to Wa, according to the Times, Adul is “proficient” in Thai, Burmese, Mandarin, and English—which enabled him to interpret for the two British divers who discovered the trapped team.

Nearly two billion people study English as a foreign language—about four times the number of native speakers. And apps like Google Translate make it possible to communicate, almost anywhere, by typing conversations into a smartphone (presuming your interlocutor can read). Ironically, however, as the hegemony of English decreases the need to speak other languages for work or for travel, the cachet attached to acquiring them seems to be growing. There is a thriving online community of ardent linguaphiles who are, or who aspire to become, polyglots; for inspiration, they look to Facebook groups, YouTube videos, chat rooms, and language gurus like Richard Simcott, a charismatic British hyperpolyglot who orchestrates the annual Polyglot Conference. This gathering has been held, on various continents, since 2009, and it attracts hundreds of aficionados. The talks are mostly in English, though participants wear nametags listing the languages they’re prepared to converse in. Simcott’s winkingly says “Try Me.”

No one becomes a hyperpolyglot by osmosis, or without sacrifice—it’s a rare, herculean feat. Rojas-Berscia, who gave up a promising tennis career that interfered with his language studies, reckons that there are “about twenty of us in Europe, and we all know, or know of, one another.” He put me in touch with a few of his peers, including Corentin Bourdeau, a young French linguist whose eleven languages include Wolof, Farsi, and Finnish; and Emanuele Marini, a shy Italian in his forties, who runs an export-import business and speaks almost every Slavic and Romance language, plus Arabic, Turkish, and Greek, for a total of nearly thirty. Neither willingly uses English, resenting its status as a global bully language—its prepotenza, as Marini put it to me, in Italian. Ellen Jovin, a dynamic New Yorker who has been described as the “den mother” of the polyglot community, explained that her own avid study of languages—twenty-five, to date—“is almost an apology for the dominance of English. Polyglottery is an antithesis to linguistic chauvinism.”

Much of the data on hyperpolyglots is still sketchy. But, from a small sample of prodigies who have been tested by neurolinguists, responded to online surveys, or shared their experience in forums, a partial profile has emerged. An extreme language learner has a more-than-random chance of being a gay, left-handed male on the autism spectrum, with an autoimmune disorder, such as asthma or allergies. (Endocrine research, still inconclusive, has investigated the hypothesis that these traits may be linked to a spike in testosterone during gestation.) “It’s true that L.G.B.T. people are well represented in our community,” Simcott told me, when we spoke in July. “And a lot identify as being on the spectrum, some mildly, others more so. It was a subject we explored at the conference last year.”

Комментарии